Affirmative action is a strategy first developed by the federal government as a way to combat racial bias in the United States. The first affirmative action policies were instituted more than 50 years ago, during the administration of President John F. Kennedy. At that time, the main focus was to protect workers against racial discrimination in hiring and job promotion.

Since that time, affirmative action strategies have moved beyond the U.S. workplace to include schools, universities, and other organizations, both public and private. Affirmative action strategies have taken many forms, including state and federal laws, court rulings, and executive orders.

But what have the results been? Has affirmative action truly achieved its goal of preventing racial discrimination and promoting equality nationwide? Well, yes and no.

Research suggests that important advancements have been made since affirmative action policies were first implemented. Affirmative action strategies have been shown to increase access to higher education, stable employment, and community participation overall. These policies have helped persons of color to enjoy more equal opportunities to build the free and happy life they want and deserve.

But the research also shows that the work is far from finished. While affirmative action has been very helpful in many ways, the statistics show that it is far from perfect. Racial inequities continue, and there is evidence that not everyone holds a positive view of affirmative action strategies.

This article takes a look at the history of affirmative action and provides important statistics on the strategy and its effects.

Education may be one of the most important areas where affirmative action policies are used; however, there is also significant controversy surrounding the use of such policies in education. In fact, many lawsuits have been filed in an effort to fight these measures, especially at the college level.

This section looks at affirmative action in education, focusing on its effectiveness in school integration and higher education. This section also examines public opinion on affirmative action in college and university admissions policy.

Diversity in Schools

Though school segregation officially ended in 1954 with the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling, the separation of races in the public school system continued to be a problem for decades. This was not a matter of law, as Brown made racial segregation in schools illegal.

But the reality is that communities were still very much racially segregated, not only due to socioeconomic factors but also because, for many decades, minorities were prohibited from buying homes in “white” neighborhoods.

This was a process known as “redlining,” and though redlining had also been made illegal in the late 1960s, the effects endured. And because children most often attend schools in the communities in which they live, the racial segregation of the public school system continued by default.

In the 1970s, busing was proposed to help end this kind of racial segregation, as it required some Black children to be bused to predominantly “white” schools outside of the neighborhood where they lived, while Caucasian children would be bused to schools in minority communities.

This, supporters believed, would help achieve the school integration so long desired. But some white families tried to get around school integration and busing requirements by moving to suburban neighborhoods in different school districts. This only sped up the so-called “white flight” to the suburbs which had begun to take place as urban areas became increasingly racially diverse.

Here are some of the important events in the history of affirmative action in primary and secondary education:

Court rulings in the 1990s scaled back on court-ordered busing, and the Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that race must not be a deciding factor in school enrollment.

A report by UCLA’s Civil Rights Project found that, while schools had become more racially integrated following the institution of busing, some troubling trends toward resegregation have emerged in recent years, which may be attributed to the repeal of court-ordered busing in many areas:

In 1968, before busing programs began, 64% of Black students attended schools where 90% or more of the student body were students of color.

By 1988, only 32% of Black students attended schools where 90% of more of the student body were students of color.

By 2016, the percentage had risen to 40%, suggesting that some resegregation was occurring throughout America (Frankenberg et al.)

A 2019 report by EdBuild found that 53% of students across the country were enrolled in districts that were not racially diverse, meaning that the student population was either more than 75% Caucasian or more than 75% non-white (EdBuild)

As controversial as affirmative action policies might have been in primary and secondary schools, the opposition was even greater at the post-secondary level. This was especially true in the American South, where the integration of college campuses was sometimes fiercely resisted.

In 1963, Alabama governor George Wallace blocked the door to Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama. He intended to bar two Black students from enrolling. He only stepped aside when President Kennedy called in the Alabama National Guard.

Fast-forward to this millennium. Though it has been illegal for decades to bar persons of color from enrolling in colleges and universities on the basis of skin color, higher education is still far from racially integrated. The number of Black and Hispanic students enrolled in elite colleges and universities is still much smaller than that of their Caucasian and Asian counterparts.

The following statistics indicate that the problem may not lie in higher education, but in the transition from secondary to post-secondary schools:

In the 2015-16 school year, 16% of high school graduates nationwide were Black, but less than 5% of students enrolled at selective public colleges were Black.

White students made up just 52% of high school graduates, but they constituted 63% of all students enrolled at state flagship schools the following fall.

In Mississippi, half of the state’s high school graduates were Black, but only 12.9% of University of Mississippi undergrads were Black (Huelsman)

While it is unclear why a disproportionate number of Black secondary school graduates do not make the transition into higher education, it appears that economic disparities and inadequate preparation and support through the college admissions process may be to blame. This includes a failure to address the social inequities and the impacts of structural racism that may lead many Black and Brown high school graduates to feel that higher education is beyond their grasp (St. Amour).

Despite these troubling figures, research indicates that affirmative action policies provide an essential safeguard to ensure equal access and opportunity for minority students:

A recent study found that 23% fewer students of color were admitted to highly selective colleges after affirmative action was banned, which supports the effectiveness of affirmative action programs (Blume and Long)

A UC Berkeley study published in 2006 found that “under reasonable assumptions, African American students will continue to be substantially underrepresented among the most qualified college applicants for the foreseeable future” and that “it seems unlikely that today’s level of racial diversity will be achievable without some form of continuing affirmative action” (Rothstein et al.)

Though race-conscious admissions programs in colleges, universities, and graduate schools have been a source of controversy, evidence suggests that support for such programs is growing. A report covering three surveys by Pew tracked the trend, as follows:

2003: 60% favorable, 30% unfavorable

2014: 63% favorable, 30% unfavorable

2017: 71% favorable, 22% unfavorable (Pew Research Center).

Interestingly, research suggests that support for affirmative action policies depends largely on how they are described or explained. For instance, a 2017 Gallup survey asked if respondents approved of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision supporting university affirmative action measures in Fisher v. University of Texas (detailed below).

The question began with: “The Supreme Court recently ruled on a case that confirms that colleges can consider the race or ethnicity of students when making decisions on who to admit to the college.”

When presented with this statement, Gallup survey respondents reacted in the following ways:

Nearly two-thirds of those surveyed (65%) said they did not approve of the Fisher decision; just 31% said they did.

In the same poll, 70% said college admissions decisions should be based solely on merit. Just 26% said that race and ethnicity should be taken into consideration to promote diversity.

The 2017 poll also asked respondents to rank nine considerations used in university admissions processes. They were to decide whether each should be a “major factor,” a “minor factor,” or “not a factor at all.”

When it came to race or ethnicity, 9% said it should be a major factor, and 27% a minor factor. But a large majority (63%) said it shouldn’t be a factor at all (Newport).

As has been seen, affirmative action has played a large — and often controversial — role in education. But education is not the only area where these policies are a major factor.

Indeed, affirmative action has also been used as an important tool to promote equal opportunity in the workforce. This section will examine the use of affirmative action in the labor sector. The effectiveness of affirmative action policies for promoting more just hiring and promotion policies will be discussed. This section will also explore public opinion on affirmative action in the workplace.

The workplace is often considered a major frontline in the battle for equal rights. And, largely, advocates for affirmative action seem to be winning, if slowly and in small steps.

The following data show promising results:

A 2012 study suggested that “government policy has contributed to increasing diversity at U.S. workplaces” between 1973 and 2003.

The same study found that female and minority representation increased more, on average, with federal contractors who were subject to equality regulations.

Black and Native American workers were the “primary beneficiaries” of the policies.

The results, though, are not entirely positive:

The same 2017 study that showed improvements in employment access and opportunity for Black and Native American workers also found that Hispanic/Latino and Asian American employment did not substantially increase (Kurtulus)

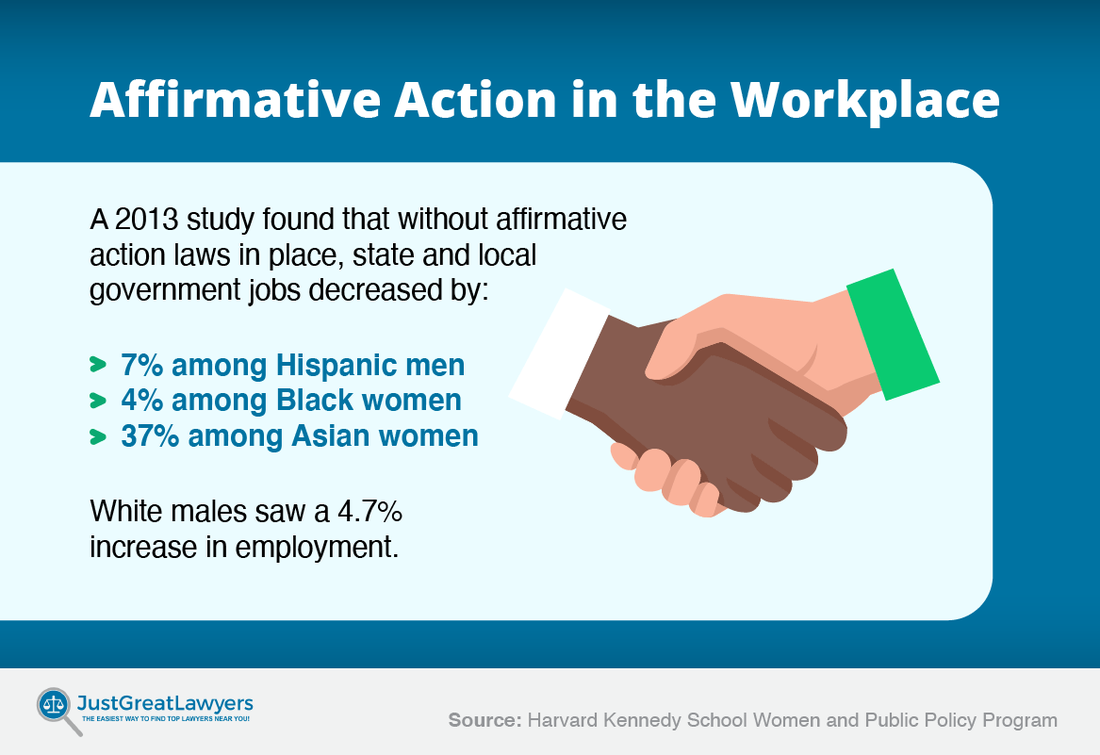

A 2013 study looked at the effects on employment after anti-discrimination laws were repealed in four states: California, Michigan, Nebraska, and Washington. The study found that the ending of anti-discrimination laws led to “a significant decrease in workplace diversity” compared with states where the laws were still in effect (Kurtulus, “The Impact of Eliminating Affirmative Action…”)

The research further suggests that, without affirmative action policies in place, labor participation decreased among persons of color, with employment rates declining by

7% among Hispanic men

4% among Black women

37% among Asian women (Kurtulus, “The Impact of Eliminating Affirmative Action…”)

At the same time, according to this study, white males saw a 4.7% increase in employment after the affirmative action ban was instituted (Kurtulus, “The Impact of Eliminating Affirmative Action…”),

As has been shown, affirmative action policies can take many forms, from laws to court rulings. But when it comes to affirmative action in the workplace, some of the most monumental steps have been taken through executive orders issued by the sitting U.S. president.

And, as will be seen, some of these important actions took place even before John F. Kennedy’s important push for affirmative action. In fact, some presidential executive orders signed in the preceding decades paved the way for the development of more formalized affirmative action strategies from the 1960s to the present.

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802. This instructed defense contractors to “provide for the full and equitable participation of all workers in defense industries, without discrimination because of race, creed, color, or national origin” (Peters and Woolley)

The primary purpose of Roosevelt’s order wasn’t to provide equal opportunity or equal protection, though. Instead, as with other wartime measures, Roosevelt’s order was meant to bring “all hands on deck.” It was another method of utilizing all available resources to fight the Axis powers during World War II. However, the Order still led to increasing recognition of the need for integration and equal opportunity.

In 1953, President Eisenhower created a Government Contract Committee. This banned discrimination based on race, creed, color, or national origin in federal hiring.

Under Kennedy’s 1961 Executive Order 10925, the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity was created (Peters and Woolley, “John F. Kennedy...”). The action helped to consolidate and expand the powers granted in previous executive orders to help promote opportunity and equality in the federal workforce.

In particular, Kennedy’s order expanded those equal protection and equal opportunity provisions to include all federal contractors, and not just those in defense, as with Roosevelt’s executive order issued two decades prior. It was also the first designed to take positive, or “affirmative”, actions in order to not simply to protect persons of color from racial discrimination in the federal workforce but to actively open up greater employment opportunities for workers of color.

In Executive Order 11246, Lyndon B. Johnson mandated that federal contractors “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin” (Peters and Wooley, “Lyndon B. Johnson…”).

Importantly, Johnson’s order was expanded in 1969 by President Nixon, who added disability and age to the criteria for groups protected under the program.

Public Opinion on Affirmative Action in Society

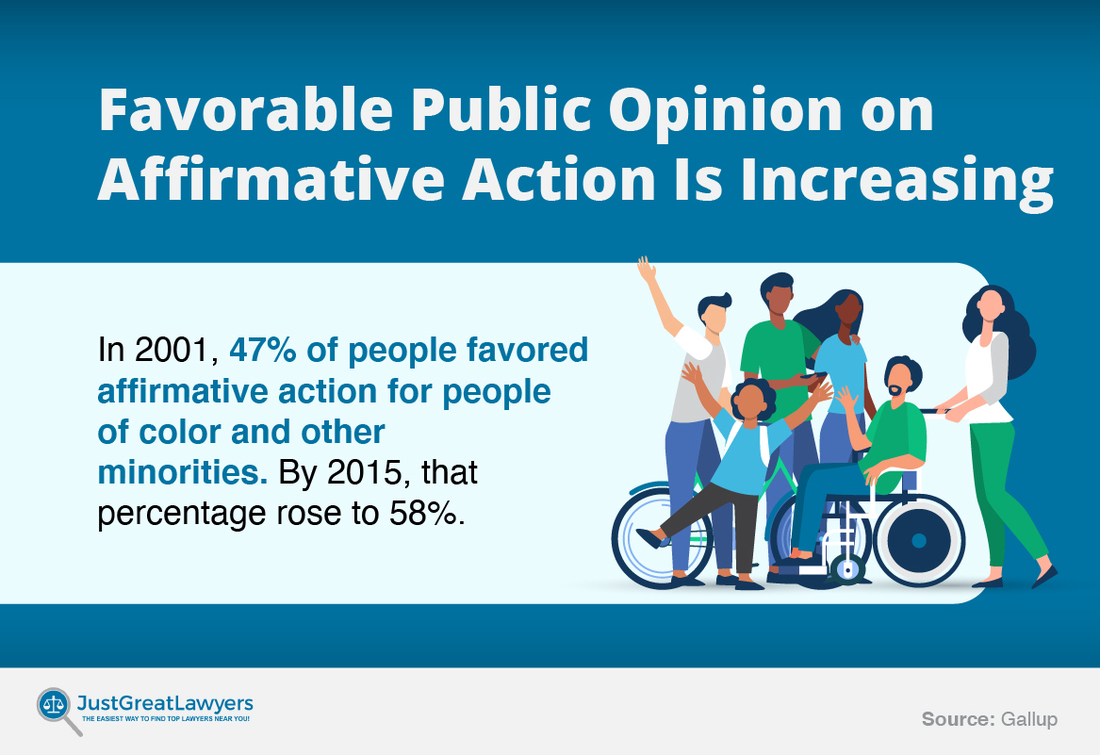

Numerous polls, surveys, and studies have shown that, in general, public views on affirmative action programs have grown generally more favorable over time.

A 2015 Gallup poll showed that 58% of respondents said they favored affirmative action for people of color and other minorities (Riffkin);

Studies also show that support for affirmative action has steadily been on the rise, increasing from 47% approval in 2001, to 49% in 2003, to 50% in 2005 (Jones);

A report by the American Enterprise Institute found that 64% of respondents favored “affirmative action programs designed to help blacks, women, and other minorities get better jobs and education” in 2003. That number rose to 67% in 2005 and 70% in 2007.

Though the statistics show favorable trends with regard to public support, these attitudes are not shared equally by all segments of the population. Polls taken between 1987 and 2015 consistently showed that support for affirmative action among Black respondents was 16-24 percentage points higher than approval rates among white respondents.

The following opinion data are telling:

1987 Harris survey: Blacks 83% favorable, whites 67% favorable

2000 Gallup survey: Blacks 79% favorable, whites 55% favorable

2015 Gallup survey: Blacks 77% favorable, whites 53% favorable (Bowman and O’Neil).

Results from a 2005 Gallup poll have also shown that ideology usually plays a far bigger role in attitudes among white respondents than Black respondents:

Among Blacks, opposition barely shifted at all among liberals, moderates, and conservatives, varying just two percentage points, between 19% and 21%.

Among Whites, 35% of liberals opposed affirmative action, compared with 43% of moderates and 60% of conservatives (Jones).

While major strides have been made in racial equality in recent decades, thanks in no small part to affirmative action, much work remains to be done. Because racial disparities in employment and education persist, the need for affirmative action continues to this day.

In light of this, recent U.S. presidents have taken steps to speed progress in racial equality through the use of affirmative action. For example, in 2014, President Barack Obama issued Executive Orders 13665 and 13672.

These orders were designed to promote greater transparency in the wages of federal contractors in an effort to decrease the gender pay gap. The move was also intended to prevent discrimination in the hiring and promotion of federal workers based on gender identity or sexual orientation.

Obama’s executive orders, though, were not entirely uncontroversial. And, in July 2018, The New York Times reported that the Trump administration was reversing some of the equal opportunity policies instituted under President Obama.

For example, the Trump administration rescinded an instruction that defined campus diversity as a “compelling interest.” The Trump administration also backed an appeal of the judge’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University.

These actions were based on the premise that affirmative action policies placed an undue burden on public institutions, undermining the argument that campus diversity provides a “compelling interest” greater than the resources spent in creating and enforcing affirmative action policies.

In addition, these actions were also based on the argument that some affirmative action policies were discriminatory against students who did not qualify for benefits and protections under affirmative action statutes.

But it was not only political and cultural resistance from some factions that led to changes in affirmative action policies. In 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a National Interest Exemption memorandum. This granted employers a waiver from some legal requirements in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. This waiver included exemptions from diversity and equality requirements for government contractors.

Affirmative action has changed over the years, developing from a simple goal — improving diversity and opportunity — into an intricate series of policies and programs.

Some of these policies and programs have been more controversial than others. But on the whole, polls show that they’ve become increasingly accepted over time. More importantly, statistics indicate that they’ve proven effective at achieving greater diversity and inclusion, even if only in part.

It remains to be seen whether affirmative action can level the playing field in the United States. Will there be a point at which we can say “mission accomplished”? Or will the struggle for equal opportunity persist into an uncertain future?

The answers to these questions remain to be seen. In the meantime, we must keep monitoring the situation and working to improve in our quest for civil rights, diversity, and equality.